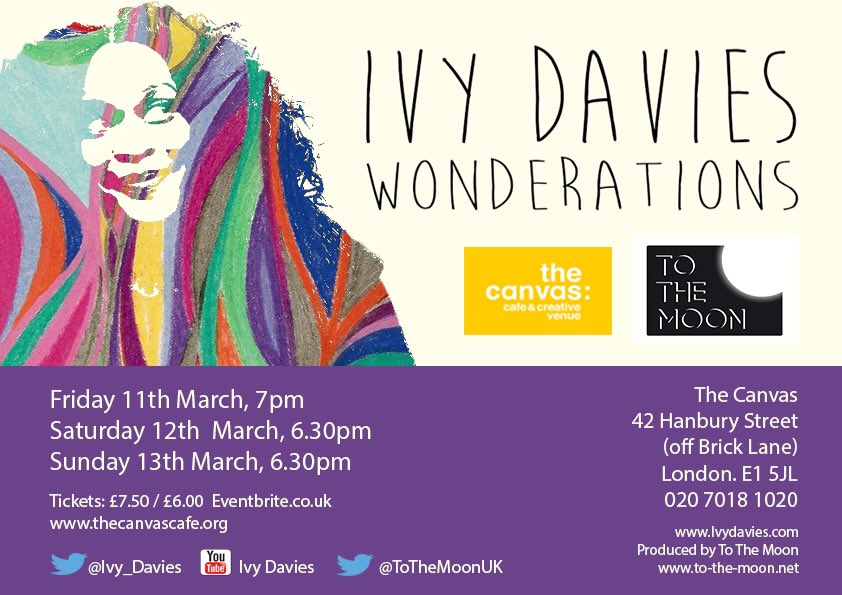

Sunday evening was a night of new discoveries. The Canvas Café, just off Brick Lane, serves homemade cakes and prosecco by the glass. It also has walls you can write on and a cosy downstairs performance space. In that space was Ivy Davies and her show Wonderations, a gentle, joyful blend of spoken word, songs from her EP and questioning whether or not Mickey Mouse is actually God. Though lacking in narrative, Davies’ performance shares issues that are particularly personal: aging and her search for identity and faith. With a touch of live art about it, Wonderations is a lovely celebration of self-acceptance akin to reading Davies’ journal.

This isn’t a visual show, but a totally aural one. It could easily be listened to through headphones or with eyes closed, though her soothing melodies and rhythms could lull you to sleep – it’s that relaxing. There are some powerful sentiments in her lyrics and poetry that deserve full attention, however. As Davies struggles to find her pre-marriage and babies self in theatrical songs and rhymes, one can’t help but to relate to her frustration with finding her true identity buried under all the nonsense life throws at us. We all find ourselves wasting hours on social media focused on constructing an image, or immersing ourselves in work and forgetting to just be present in the world for lengthy periods, but Davies exhorts us to let all of it go. She’s like a life coach, but a gentle one who uses cuddles rather than shouting.

This cabaret-esque structure feels conversational, but is precisely and satisfyingly scripted. There’s no plot to speak of, but with Davies wearing the form like her own skin, it works. Her spoken word isn’t the pounding, angry sort I’m accustomed to; it’s full of flowers, sunshine, rain and claiming her own ground. Davies has an immovable strength and presence, but one that overflows with positivity. Less connected from her celebratory songs and spoken word is what feels like an internal monologue where in looking for faith, she wonders if God is actually Mickey Mouse. He’s been seen around the world at the same time, and has plenty of purchasing power. It’s a wonderfully funny, and pointed, argument, though less clear on it’s place in the show’s structure.

Ivy Davies’ Wonderations is a hard show to pin down, but it doesn’t apologise for that. I’m pretty certain that she’s confident enough to not care what anyone thinks of her work, but the themes it contains are universally human presented in an easily digestible format. An excellent event for a quiet Sunday evening, particularly with a slice of cake and a glass of prosecco.

The Play’s the Thing UK is committed to covering fringe and progressive theatre in London and beyond. It is run entirely voluntarily and needs regular support to ensure its survival. For more information and to help The Play’s the Thing UK provide coverage of the theatre that needs reviews the most, visit its patreon.