by Laura Kressly

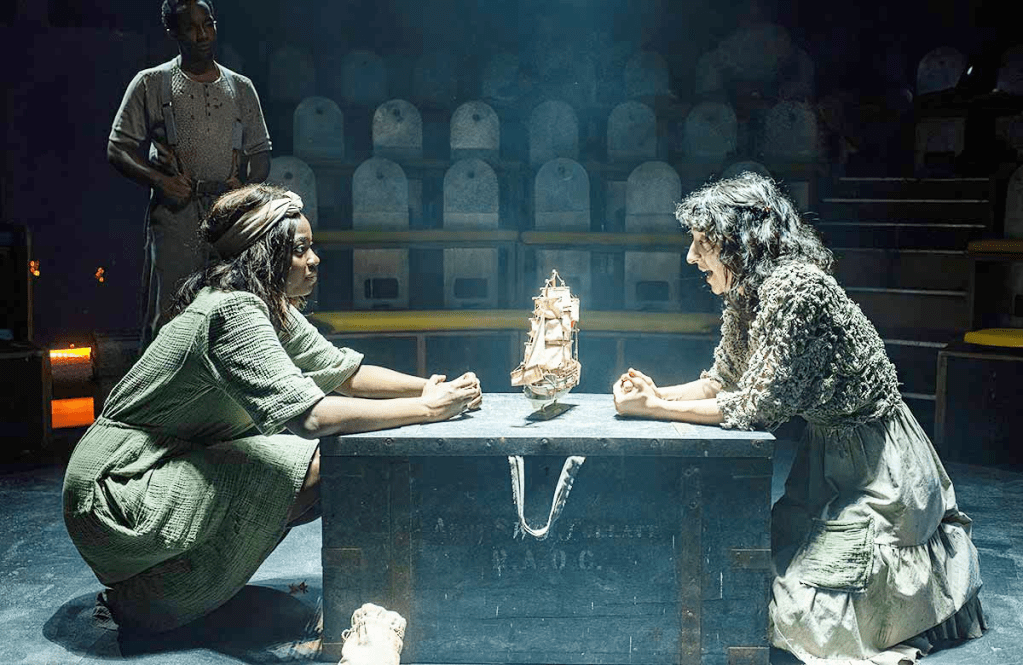

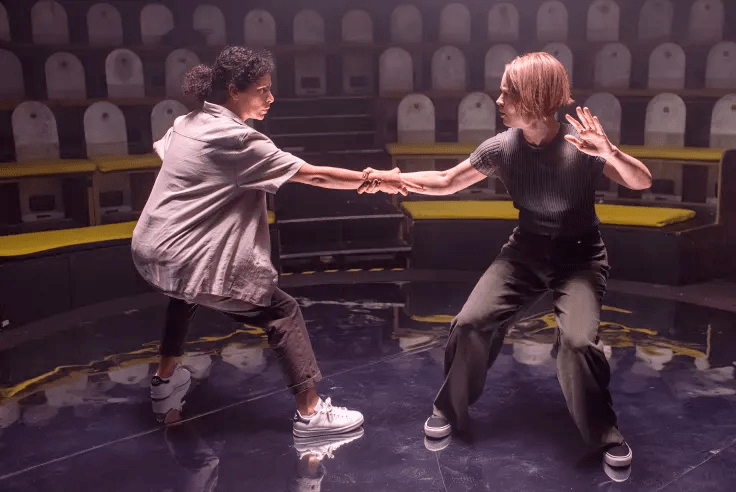

At the start of this piece that is definitely not about Hong Kong, we are asked not to take photographs. This is because the performers, who are absolutely not from Hong Kong, could face persecutions under China’s National Security Bill if they were caught making a show about Hong Kong. But this is all hypothetical, because this physical theatre show is not about Hong Kong.

Continue reading