Nearly twenty years ago, I went to my first Cirque du Soleil show in New York. A young teenager and already obsessed with theatre and performance, I was blown away by the colour and spectacle, having never seen anything like it before in the fourteen years that I’d been on this earth. I have no concrete memories of the show, just flashes of light and colour, and feeling impressed. I looked forward to see if Amaluna, inspired by Shakespeare’s The Tempest, would live up to my juvenile memories.

It took a while to find out. First, I had to meet my critic friend, who had invited me as her guest, at door 6 at 7:30. I approached Royal Albert Hall from the side closest to Exhibition Road and found myself at door 3. Not being familiar with the venue, I picked a direction and soon found I was going the wrong way. Considering it’s a circular building and I was early, I carried on and found myself at door 6.

WHAT SHEER HELL IS THIS? At door 6 was Cirque’s version of a red carpet (it was blue), a queue of luxury cars out of which vaguely familiar people emerged in black tie and evening gowns, bright lights and hordes of shouting paparazzi. A few cold looking performers in costume posed for photographs, film crews conducted interviews and vicious looking security guards hovered, ready to move on anyone that looked like they didn’t belong.

I’ve been to a lot of press nights, but this was incomparable. More like a film premiere or awards ceremony, Cirque at some point took the circus outside the venue and into the media and celebrity world. When did this happen? Or more importantly, why? Does Cirque really need the publicity so badly that they pander to the vapid world of Big Brother contestants and paparazzi? And how was I supposed to find my friend in this mess?

Giving wide berth to this bright and shiny, “OK Magazine Live!” shitshow, I carried on to the other side of the large foyer that the blue carpet led to. Fortunately door 6 was duplicated opposite and the nice usher on the door let me wait in the warm. I still managed to be early. The performers across the foyer still looked cold; it dawned on me that they had to be onstage doing acrobatics in less than an hour and that they were either understudies/doubles or Cirque is more interested in photo ops with celebs than the wellbeing of their performers. I desperately hope it’s the former.

Anyway, the show itself. Nearly. We had great seats in a box allocated for press but I didn’t realise at first just how good they were. Or rather, how expensive, until critic friend informed me what they were retailing for. My initial reaction was an inner explosion of flabbergast, “people around us paid HOW MUCH for this show?” Then I realised: press get their tickets free, as does the wafting, gormless army of famous people, so how much is Cirque actually making out of this press gala? Especially considering the post-show reception (we declined our invitation to attend) and the swathes of empty seats in the upper galleries. These are the cheapest seats, but on a press night, why are they empty? Were they marked up so much that they weren’t bought? Are people not interested in Cirque anymore? (In which case, they desperately need the media attention.) Or, did Cirque keep them vacant so plebs didn’t gawp over their famous fellow audience members? Regardless of the reason, none of the prospective answers are positive.

NOW for the show. Really.

I love when theatre and performance makers mess about with Shakespeare. It can prove his work is still relevant and opens the possibility of a new perspective or insight. The programme states that this is a female-driven show: Prospero is now Prospera, and Amaluna is Miranda’s empowering coming-of-age story. The band is entirely female, as is most of the cast. A feminist adaptation of a Shakespeare play for circus? It should be brilliant, and exceed my youthful memories of my last Cirque show.

It’s not brilliant. Sure, it’s bright, colourful and a consistent sensory overload. The skill-set of the performers is top notch. There are acrobats, aerialists of all kinds, clowns, Chinese pole performers, and juggling. It’s technically impressive. It’s easy to get swept away by the spectacle of the whole thing.

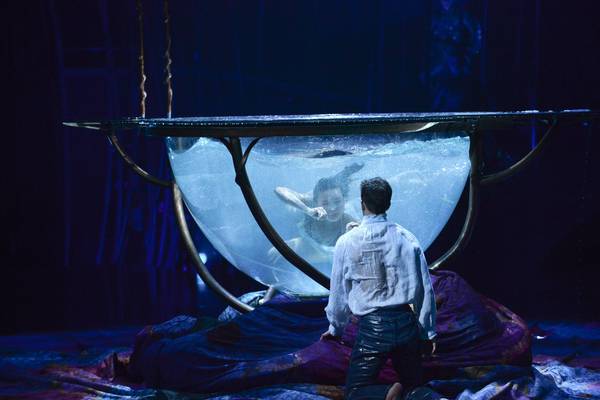

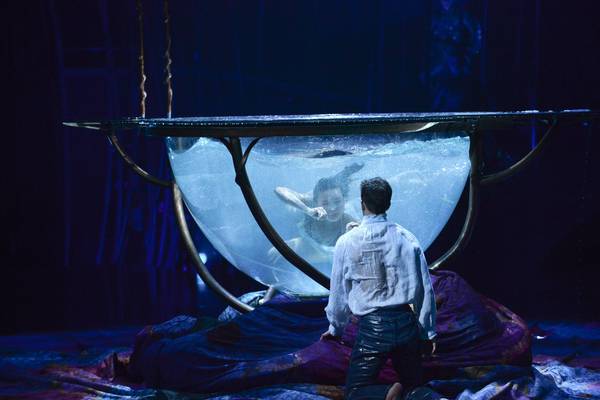

There’s little substance, though. They story is a vague framework for the circus acts and spectacle. Most importantly, the supposedly empowering female narrative is anything but. Prospera throws a party for her daughter Miranda, who then bathes in the light of the aerial hoop performing Moon Goddess who bestows her with a gift of a glass sphere. It’s an obvious metaphor for Miranda’s womanhood/menstrual cycle, and a cringy one at that which doesn’t contribute anything to The Tempest aspect story. Miranda also meets a prince who has washed up on their island in a storm. Called Romeo rather than Ferdinand (dear god, why???), Miranda immediately falls in love with his sculpted, often shirtless body. Her best friend Cali, a half-lizard-half-man creature, is jealous of the man who’s taking away Miranda’s attention from him. The two male characters compete for young Miranda’s attention and the pretty, shipwrecked Romeo was always going to win, gifted with a wedding and all. It was like an old school Disney film. Empowering to women? No, no, NO. The narrative presented was about as disempowering as you can get, particularly when you factor in the creepy plot points of an unseen Romeo watching Miranda bathe and hand balance in white shorts that become nearly transparent from the water (You can see EVERYTHING. I’m pretty sure I could see up into her stomach during the splits.), and Cali abducting her into the heavens to keep her to himself. Also consider for a moment that in Shakespeare’s version, Caliban raped Miranda and is enslaved by her father as consequence. Plus, if this is Miranda’s coming-of-age celebration, she’s how old? Sixteen AT THE OLDEST. And she get married at the end of a story that spans no more than a couple of days? This is supposed to be a piece of performance that empowers women.

There’s also plenty of creeping elsewhere in the show. The two clowns, one a nanny to the young Miranda and one a washed up sea captain. Mainha and Papulya are overtly sexual, and as cringy as the Moon Goddess. There’s classical Commedia influence in the pratfalls and lazzi-like sketches full of groping, arse kissing and manipulation. I get that circus performers have to wear tight clothes for their work, but the men are often topless for no apparent reason and there’s more female flesh on display than needs be.

Ignoring the narrative and theme, the individual acts and the show of it is celebratory, fun and a showcase of skill. However, Cirque as a vast, commercial institution raises some concerns, and the perception of female empowerment and celebration by their creative and marketing team when the reality is the opposite is not only highly disturbing, but a sign of endemic patriarchal complacency about what is an acceptable lens to view womanhood through in the performing arts.

The Play’s the Thing UK is committed to covering fringe and progressive theatre in London and beyond. It is run entirely voluntarily and needs regular support to ensure its survival. For more information and to help The Play’s the Thing UK provide coverage of the theatre that needs reviews the most, visit its patreon.

Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film Romeo + Juliet transformed a young generation into Shakespeare fans. Dan Poole and Giles Terera were training at Mountview at the time of the film’s release. They previously weren’t keen on Shakespeare’s plays what with their difficult language and having to read them at school. But, Romeo + Juliet changed all that. These avid Shakespeare buffs joined forces to make a documentary that explores why people don’t like Shakespeare, and to make the Bard more accessible to those ruling him out as boring or irrelevant. Over four years, Terera and Poole travelled around the world and interviewed prominent actors, audience members, people on the street and passionate theatre makers about their attitudes towards Shakespeare. Funny and relaxed, Muse of Fire feels more like a goofy road trip with your mates rather than a dry, academic film as the passion and love for Shakespeare’s work always shines through.

Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film Romeo + Juliet transformed a young generation into Shakespeare fans. Dan Poole and Giles Terera were training at Mountview at the time of the film’s release. They previously weren’t keen on Shakespeare’s plays what with their difficult language and having to read them at school. But, Romeo + Juliet changed all that. These avid Shakespeare buffs joined forces to make a documentary that explores why people don’t like Shakespeare, and to make the Bard more accessible to those ruling him out as boring or irrelevant. Over four years, Terera and Poole travelled around the world and interviewed prominent actors, audience members, people on the street and passionate theatre makers about their attitudes towards Shakespeare. Funny and relaxed, Muse of Fire feels more like a goofy road trip with your mates rather than a dry, academic film as the passion and love for Shakespeare’s work always shines through.