By Luisa De la Concha Montes

What makes us human? Is it the capacity to feel? Or perhaps our experiences, and how we can sew together memories to create an identity that we can call our own? Is it how we develop relationships with other humans? The ease in which we crave proximity, or fall into patterns of desire? The Employees, a play based on the International Booker Prize-nominated novel by Olga Ravn and directed by Polish theatre artist Łukasz Twarkowski, poses these questions to the audience in quite an unconventional manner.

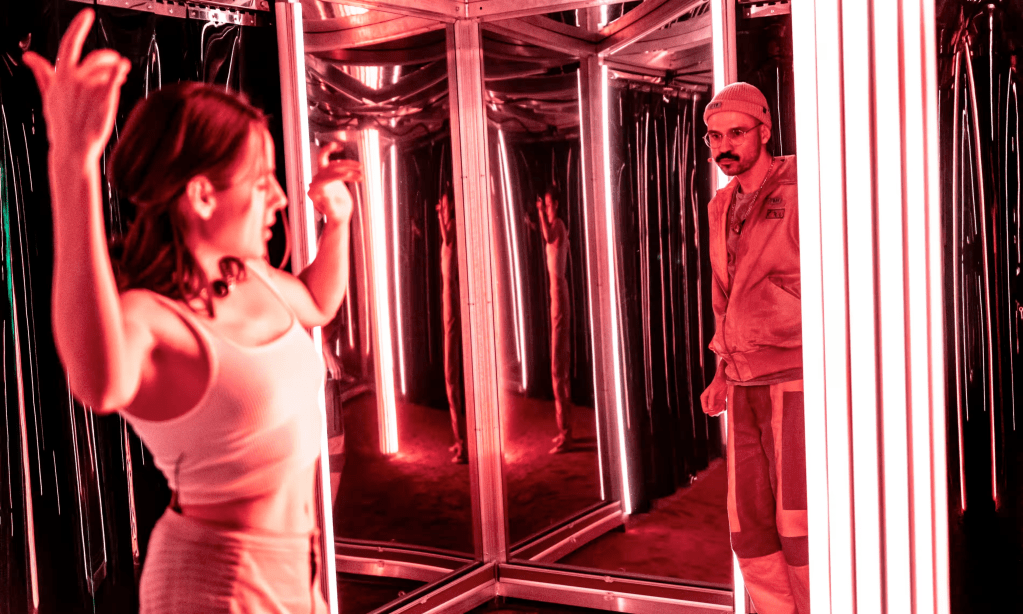

The theatre serves as a test tube where strange sci-fi experiments are taking place. Audience members are invited to be part of it from the get go: there are spaces to sit in front of and on the stage itself. Over the speakers we are told that seating is unreserved, and members of the audience are welcome to move around the space to experience the performance from different points of view. However, only the employees can enter the box in the middle.

This box serves as an inverted panopticon in which the employees live and work. The catch is that for every human employee, there is an identical humanoid version of themselves. And as the story progresses, the humanoids become more human, while the distance from the Earth is making the humans forget what made them human in the first place.

Throughout the play, the actions of the employees are captured by two camera operators that follow the actors around the space in a carefully choreographed manner, reminiscent of an OK Go music video with sleek transitions and rhythmic light movement. Their actions are then projected onto the eight screens on the walls of the box.

As we are allowed to get as close as we want to the box, we enter a fragmented narrative, where we can choose between seeing the real-life action through the apertures in the box or seeing the live stream on the screens, constantly asking what is real and what is not; as some of the material projected on the screens is pre-recorded. The projections are expertly knitted together, and the camera work is incredibly well coordinated, to the point that I question the decision not to have the camera operators listed as members of the cast.

The execution is spotless and the show is well rehearsed, with every actor following their movement cues in time while still remaining in character. To hold the stage for over two hours, remembering the dialogue and showcasing a wide range of emotions is a feat that does not go unnoticed. In a couple of scenes, the employees play each other songs that remind them of Earth. And through their expressions and their dancing, we are launched into intense empathy, remembering what truly makes us human. As such, the actor’s capacity to slow down the rhythm within the speed of the stage is one of the strongest elements of the play.

The scene that stuck with me the most was when Cadet 4 (Robert Wasiewicz) tells Cadet B19 (Daniel Dobosz) how once, he was on his way to meet someone that he “really needed to hold”; someone he loved, someone he missed. On the way there, he got stuck because there were roadworks, and the workers themselves were having a smoke, instead of working. Cadet B19, unable to connect with the first part of the story (the part about needing to hold someone to the point of desperation) asks why he didn’t report the workers with their supervisor. This short fragment contained so much meaning: the inability of machines to feel the weight of emotions; and how everything, in the eyes of machines, is a problem-solving challenge.

However, at the end of the play, I was unsure of what exactly I had seen; there was no conflict or plot, just a series of random moments, knitted together by a hunger for movement. The space is the show, and perhaps that is the point: to take technological advancement to its highest form, crafting a story that is not a story without a multiplicity of screens to hold it together. Perhaps the problem is me: Unlike AI, I am unable to grasp multiple narratives at once; churning out conclusions simultaneously. By the end of it, I became confused, tired even.

But maybe that is the point? The conflict between virtual truth and physical truth can only be explored through a hyper-fast universe that effectively accomplishes our wildest technological dreams, and in the process, alienates the human side of ourselves that is still clinging to linear storytelling.

The Employees ran through 19 January.

The Play’s the Thing UK is committed to covering fringe and progressive theatre in London and beyond. It is run entirely voluntarily and needs regular support to ensure its survival. For more information and to help The Play’s the Thing UK provide coverage of the theatre that needs reviews the most, visit its patreon.