By Luisa De la Concha Montes

We all spend too much time on our phones – there is no doubt about it. So, how can phone addiction be explored, in 2024, without relying on redundant tropes? Phone, a play written and directed by Sam Taylor explores our overreliance on digital media through the distant, yet loving relationship between four siblings: Helen, Issy, Harvey and Luke. They find themselves in a holiday resort in Hastings, the same one they used to frequent as children every summer.

Luke (Felix Warren), the youngest, is a gamer who spends endless hours playing campaigns until late hours of the morning to align his schedule with his best friend, who lives in China. Issy (Jessica Garton) is still in college, and she is dating an older guy. She anxiously reveals that he is a photographer, and that she will never be able to compete against the young, thin models featured on his Instagram. Finally, Harvey (Ted Walliker), has been in a long-term relationship with Sara (Lauren Koster), but he is struggling to commit fully – and is unaware of how this is affecting Sara.

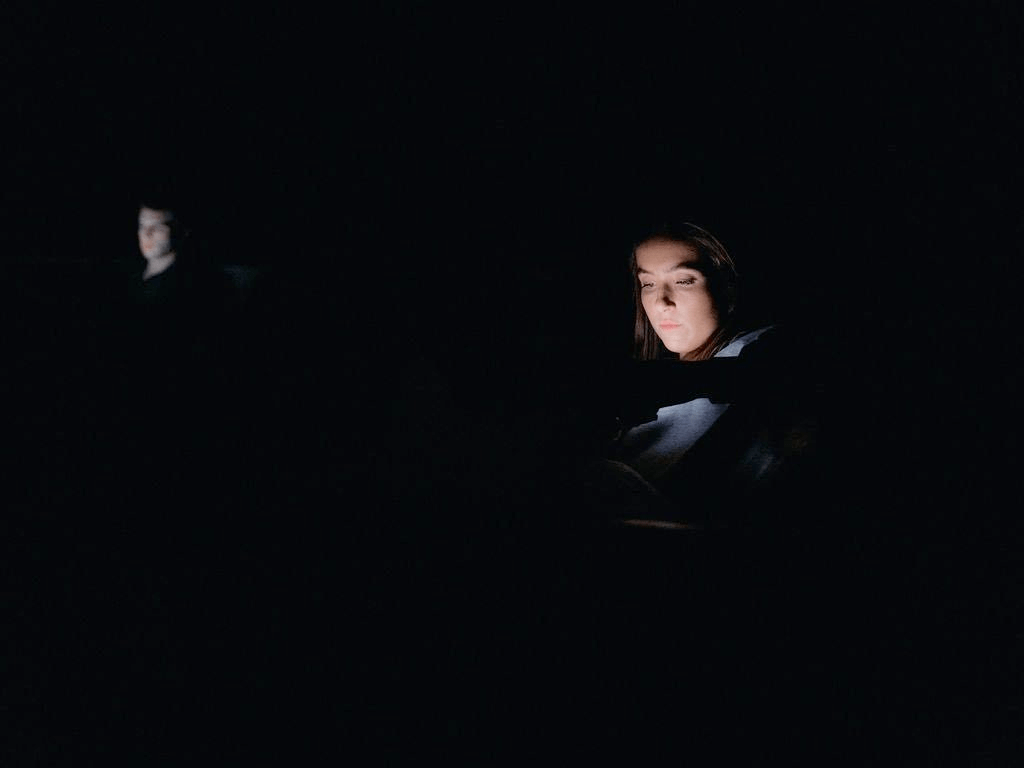

The world of the three youngest siblings is explored through the eyes of Helen (Flora Ashton) – the oldest sister, a free soul who has spent a fair amount of time abroad, and who is still figuring out her place in the world. From the get go, it becomes evident that Helen grew up in a phoneless world. The opening scene is almost too painfully familiar: four beds, with three characters mindlessly scrolling on their phones. The absent company of three bodies in the same space, yet fully separated by their screens feels awkward in the context of the theatre, yet there is an underlying sense of sadness. As Helen walks around the hotel room, unpacking, and trying to create a physical connection between herself and her siblings by sitting close to them, we understand that the distance between them is the result of a deeply ingrained generational culture war.

Despite the digital nature of the topic at hand, the stage design embraces tactility. The look and feel of a room in a budget family hotel, the creases and folds of the white bed sheets, the clattering of the dishes as the bellboy, Reece (Matt Wake), brings breakfast in. These small details resonate with Helen’s perspective, showing that, as tempting as the virtual world may be, the real, physical world is still ticking along.

This is further emphasised by Reece’s character, who awkwardly has to remind the siblings that they know each other from childhood; as they all used to play together every summer. Reece’s character, who is aptly brought to life by Wake’s honest and endearing performance, serves as a mechanism for nostalgia. He embodies the childhood the siblings once had, subtly reminding us that any child born after 2012 may never be able to have a childhood where imagination and play surpasses digital interactions. Additionally, his character also helps us understand the class struggle that plays into this dynamic; when Harvey asks why he is still a bellboy at the hotel, Reece has to remind him that not everyone can afford his lifestyle.

Writer Sam Taylor explains that the play was born out of a desire to tackle the impact smartphones are having on young people’s mental health. The direct effect that this may have is best explored by Issy’s character – a highlight of the show. Garton delivers each line with a hilarious familiarity, really tapping into the diva teen persona. However, under the rolling eyes and annoyed sighs, her character reveals a tender humanity that is truly charming. For instance, in a short interaction with Helen that starts as a funny TikTok-told-me-that rant, we realise that Issy is an incredibly anxious character, with a very real fear of death.

The culprit of the play is laid out to the audience during an argument between Helen and Harvey. He does not understand why their father insists on going to Hastings every year. When Helen tries to explain her dad’s interest in history, and the meaning of belonging, history and heritage, it becomes evident that no amount of words will ever breach the gap between Helen’s and Harvey’s perspective of what is ‘real’ and what has true value.

Going back to the initial question, Phone explores the overreliance younger audiences have on digital media without being redundant because it taps into what makes each character human; and how digital interactions have pushed them away from each other, and into an unknown and often lonesome direction. With a great cast of characters, a dynamic dialogue that never drags, and a plot twist that ties every loose thread together, Phone goes beyond being a cautionary tale about the danger of social media; it is a beautifully woven story about family trauma, resilience and the many shapes care can take in a digital age.

Phone runs through 12 November.

The Play’s the Thing UK is committed to covering fringe and progressive theatre in London and beyond. It is run entirely voluntarily and needs regular support to ensure its survival. For more information and to help The Play’s the Thing UK provide coverage of the theatre that needs reviews the most, visit its patreon.