by Luisa De la Concha Montes

Led by the Wind is a queer story that follows K (Kiki Ye), a young woman from Fuyang, China living in the United Kingdom. She has been convinced by her family back home to go on a blind date with Bryan (He Zhang), who, according to her family’s standards, is the perfect husband material. As their relationship progresses K starts zoning out, sinking deeper into beautiful dreamscapes with Windy (Vivi Wei), a mysterious woman that represents K’s deepest queer desires. In order to unveil the process of writing this piece, and to deconstruct the complexity of K’s character, I caught up with director Kiki Ye.

The show starts with K asking members of the audience if they would like a cup of tea or coffee. It is unclear if the play has started: there are no sound effects and the lights are still on. K boils water for members of the audience while telling us about the differences between English tea and Chinese tea. She draws sweet correlations between herself and the cup of tea she is making, which is a blend between Chinese tea and oat milk: “This cup of tea is strange, weird and hard to define, just like myself, a migrant artist in the UK.”

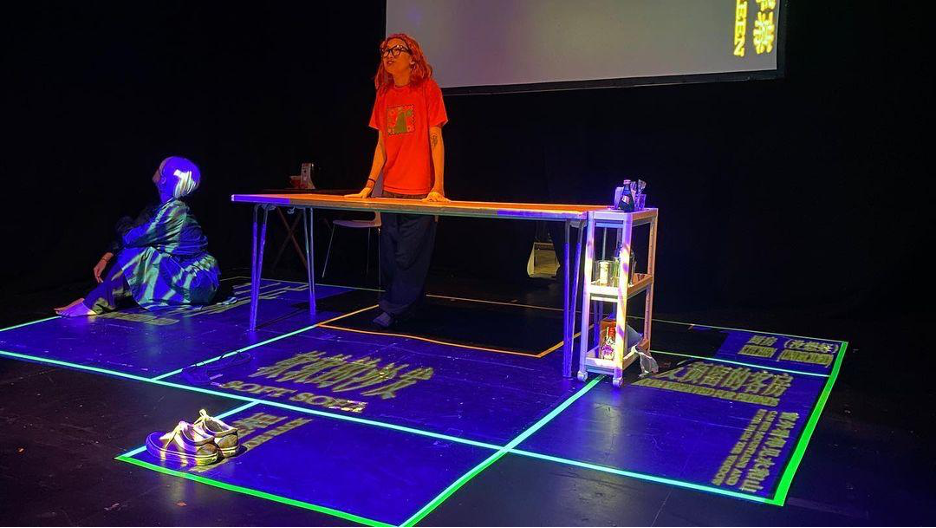

After this initial scene, the play’s rhythm changes, embracing abstraction and leading audiences inside K’s mind. In one of the key scenes, which draws a clear contrast between the life K desires with Windy and the life she has with Bryan, a projection is used to divide the stage floor into different rooms. Initially, Bryan goes around the room, stating how his and K’s flat is going to be laid out – without attempting to get K’s input. Later on, when K is dreaming, she walks around, explaining to the audience how she would lay out her own flat if she moved in with Windy. When talking about this, Kiki explains: “Projection is not just a technique. It is a new frame that opens in front of the audience, inviting them to question what is real and what is fiction.”

Each subtle difference is heavily infused with meaning, making viewers reflect on gender dynamics, women’s freedom (or lack thereof) and the difference between queer and straight spaces. For instance, Bryan wants the biggest room to be the bedroom, and the extra room to be for their future children. Contrastingly, K wants the biggest room to be the TV room for watching movies she loves, and the extra room for hosting friends. By exposing the differences between how K acts, and how K actually feels, audience members explore the “contrast between the public and the private self.”

She adds, “instead of having a conventional black box, I wanted to invite audiences to go deeper, into multiple journeys with projections and moving images.” Through this process, audiences are constantly transported into a “new space or layer in the show.” Later in the play, there is an eight-minute-long sequence where K and Windy watch a scene from K’s favourite film, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (春江水暖). This scene is a risk-taker. The danger, as Kiki acknowledges, is to “show the beauty of duration without losing the connection with the audience.” Surprisingly, it works. As the screen shows the male character in the film swimming, Windy’s character starts swimming in front of the screen and K’s thoughts are projected as subtitles. The play between words and shadows, and Windy’s dexterous fake-swim is so beautifully coordinated that it creates an image that is hard to forget.

The rest of the play jumps between K’s dream-world and the real world with Bryan, creatively exploring other feminist issues such as Chinese beauty standards and K’s struggle with her family’s expectations. Will she give in, marry Bryan and have a family, or will she accept the consequences of living as a lesbian artist? The conclusion is vague. K’s character submerges so deep into the metaphors, that it becomes unclear to audience members what actually happened. What is clear, however, is that K doesn’t come out to her family, which is a deliberate creative choice: “I wanted to explore imperfect women, not a hero. K still cares about her mother and her hometown and does not want to let them down by coming out. Like queernees itself, “this show is a process, rather than an outcome.”

The beauty of this approach is that it does not deny the transformative power of her short-lived, imagined affair with Windy. When asked if she would be able to perform this play back home, Kiki’s answer is direct: “K is a lesbian artist. If I wanted to, I would have to cut the romantic part between K and Windy and switch it into a friendship.” Therefore, by creating this queer utopia in her head, K finds a way to exist comfortably in both the real world and her dream world. In other words, she deftly embraces the liminal space of that which is left unsaid – voicing a story for those who do not have the cultural and social privilege to live an openly queer life, such as LGBTQ+ communities in Mainland China.

Kiki Ye is an up-and-coming artist worth looking out for. Her work is characterised by memorable visual metaphors, heavy with nostalgia. From ethereal dance sequences placed against homemade video projections, to conversations happening in the text box of K’s phone, each frame in Led by the Wind feels like a digital postcard exploring the fringes of liminality. At times, it is hard to tell where K ends and where Kiki starts, and she recognises this with a sobriety that I wish was more common in art that explores the personal: “For me, it doesn’t matter what parts of the story are fictional and what parts are real. For K and for me, this show feels real.”

Led by the Wind is a work-in-progress piece written and directed by Kiki Ye, and devised by Ensemble Not Found, an East Asian collective, exploring the limits of performance through technology and collaboration. He Zhang was the associate director, Ting-Ning Wen was the stage manager, Xiaonan the movement instructor, and Jovienne Jin did the sound design. Diana Miranda and Jovienne Jin worked on the dramaturgy. It ran at Applecart Arts on 15-16 August.

The Play’s the Thing UK is committed to covering fringe and progressive theatre in London and beyond. It is run entirely voluntarily and needs regular support to ensure its survival. For more information and to help The Play’s the Thing UK provide coverage of the theatre that needs reviews the most, visit its patreon.